All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Investigation on the Pharmacological Activity of Nanoactive Single Components of Ethyl Acetate Extracts of Lamiaceae Plants

Abstract

Introduction

Lamiaceae is the name of a family of aromatic plants, which are traditionally used as herbal medicine. There are not many research articles found in the literature regarding the biological study of nanoforms of the Lamiaceaefamily. However in recent years, there were few studies exhibiting the biological properties of plants from the same family. The stem and leaves of three plants from Lamiaceae family of Plectranthus genus, namely Coleus amboinicus Lour, Coleus rotundifolius Lour, and Coleus zeylanicus Lour were subjected to extraction using various solvents with different polarity index. Among the extracts, the ethyl acetate portions were subjected to various pharmacological studies. Through this study, evaluate the antibacterial activities of extracted compounds and their nano forms.

Methods

Single compounds were obtained in each extract, which were characterized by UV, IR, and NMR and LC-MS techniques. Nanoporous materials of the same type were prepared by solvothermal and sonication methods. The obtained nanoporous materials were then impregnated on chitosan and their pharmacological evaluation was carried out.

Results

All compounds isolated from the plants show a minimum assay of antibacterial properties in their nanoforms. A better performance was obtained for Coleus zeylanicus Lour.

Discussion

Selected compounds from plectranthus amboinicus, plectranthus rotundifolius and plectranthus zeylanicus were converted to their nanoforms. These nanoforms were studied by antibacterial analysis. Some of these nanoforms combined with chitosan and their antibacterial activity were studied. Extracted compound from plectranthus zeylanicus using ethyl acetate extract were selected for this study. Bioavailability, chemical potential, nutritive contents and efficiency are the implications of these Compounds. Sustainability, specificity, reproducibility, and solubility of prepared compounds are the limitations of this study.

Conclusion

Chitosan impregnated Coleus zeylanicus Lour had high antibacterial potential against E.coli. growth.

1. INTRODUCTION

In many of the countries in the world, there is a usual practice of utilizing plant materials as medical components for the prevention and curing of certain deceases [1-5]. A wide variety of plants have been extensively used for this purpose [6, 7]. A secret knowledge, are usually inherited or transferred from ancestors, for various remedies are observed in many parts of the world [8]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 75% of of the total world’s population relies on plant-based medicines [9]. It is worth noting that Many of these plant-based medicines work well for instant relief.

Medicinal plants play a vital role in their raw form or mixed with various ingredients for treatment of various diseases [10-13]. Processing of the medicinal plants, in most of the times, which leads to the concentration of its required ingredients. However, in some of the cases,, the increased concentration may not be useful as it causes other problems, such as headache, diarrhea, etc [14, 15]. The thorough studies of optimization and identification of the contents of the medicinal plants in various forms are essential to understand their pharmacological effectiveness [16-18].

In Ayurvedic medicines, the plants belonging to the Plectranthus (mint) family are used for healing various diseases owing to its nutritional, pharmacological, and phytochemical properties [15, 19-21]. Among this family of plants, their leaves and stems are directly used to make oral medicines in most cases [22-24].

In this communication, we describe the extraction of the Plectranthus genus, namely Coleus amboinicus lour, Coleus rotundifolius lour, and Coleus zeylanicus lour, using ethyl acetate. Coleus amboinicus our. belongs to the Lamiaceae family and has an extraordinary potential to heal various diseases such as fever, allergic reactions, skin allergies, and itching, asthma, cough, cold, rheumatism, arthritis, dysentery, diarrhea, bloating, indigestion, constipation, dyspepsia, and epilepsy [1, 25]. Coleus rotundifolius Lour., also known as Chinese potato can be used as an ingredient in many traditional medicines. It has the ability to treat constipation, dysentery, urinary infection, eye disorders, hypertension, menstrual cramps, diabetes, diarrhea, nausea, throat and mouth infection, cancer, etc., and various skin diseases like eczema, acne, diabetes, burns, abdominal pain, sores, insect bites, allergies, and wounds [26, 27]. Coleus zeylanicus lour is an aromatic herb widely used as a folk medicine in Sri Lanka and India. The plant as a whole or as various extracts is used for the therapeutic applications of ulcers, asthma, cold, dysentery, diarrhea, small pox, eye diseases, dermatitis, throat infection, cough, fever, and atherosclerosis [28]. Plectranthus plant extracts are not is only used in medicine, but also has wide applications in engineering, especially in materials science and nanotechnology [29]. These observations encouraged us to utilize these three plants for our phytochemical studies.

2. EXPERIMENTAL

2.1. General Considerations

The green plants planted in our farm were collected, washed, and dried in the shade. They were subjected to polarity index extractions, using organic solvents of increasing polarity.

The specific extract of all the plants was purified and characterized. These components and, their nanoforms were subjected to pharmacological evaluation. Nanoforms were obtained by using the solvothermal method and the sonication method with ethyl acetate as solvent.

2.2. Materials

The plants used for our study were Coleus amboinicus lour (PA) [Coleus Aromaticus (scientific name), Mexican mint (common name), Panikoorka (name in local language)], Coleus rotundifolius lour (PR) [Coleus poteto (scientific name), Chinese potato (common name), Koorka (name in local language)] and Coleus Plectranthus zeylanicus lour (PZ) [Coleus Zeylanicus (scientific name), Iruveli (common name), Chumakoorka (name in local language)]. These plants were collected from Peravoor town in Kannur district (Kerala, India) and identified by a botanical expert (Dr. Pramod C., Assistant Professor, University of Calicut).

They were stored in the chemistry laboratory of Kannur University, Kerala, India, under the specimen names Ethyl acetate B1, Ethyl acetate B2, Ethyl acetate F and Ethyl acetate J. Ethyl Acetate (Merk, India) was distilled before use and Chitosan (Low molecular weight with 90% DA) was purchased from Sisco Research laboratories, India. Acetic acid (99.8% purity) was obtained from Hi-Media, India. The bacteria Escherichia coli (E.coli) was provided by the Department of Health Sciences, University of Calicut.

2.3. Instruments

UV-Vis spectra were recorded from 200-800 nm on a Jasco V-650 spectrophotometer by using ethyl acetate as the solvent. Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded using the Jasco model 4100 FT-IR spectrometer. The samples were taken as KBr pellets. Hitachi, SU 6600FESEM, was used for the field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESCA) studies. An Agilent 6100 Series Quadrupole was used to run Liquid Chromatography combined with Mass Spectra (LC-MS). The NMR spectra were recorded (at 400 MHz - 1H, 100 MHz-13C) on a Bruker-400 MHz spectrometer instrument. The chemical shift values were reported relative to Me4Si (1H) and CDCl3 (13C) as internal standards and the coupling constant was given in Hertz (Hz). Sonication was carried out on a LOBA Life Sonicator (1.5 L). Melting points were measured on the Dalal melting point apparatus, capillary type up to 360°C.

2.4.Methods

2.4.1. Extraction Method

5 Kg each of all three plants (including leaves and stems) were collected and weighed accurately. It was dried in the shade and powdered. 30 g of the powder was subjected to the extraction methods. The following four methods were used for the preliminary extraction of samples.

a. Percolation: It is the continuous downward displacement of the solvent through the material under study to get an extract. We employed this method for obtaining most of the plant extracts. There was a slow increase in color change in this process. However, the complete extraction was doubtful.

b. Infusion: It is the extraction of chemical compounds from a plant in a solvent.

c. Maceration: It is a process of softening plant materials by soaking them in a solvent.

d. Decoction: It is the extraction of the essence of a plant by boiling the plant materials.

In addition to the percolation, we used infusion, maceration, and decoction methods for all the samples to ensure maximum extraction.

The extract after the preliminary methods was transferred to the round-bottom flask and extracted using solvents on the polarity index for a time span of three hours each. It was assured that in each case, the former solvents were completely removed before the use of the next solvent. The solvent extraction sequence was based on increasing polarity.

Accordingly, the hexane extract was collected initially. Then, the ethyl acetate fraction was collected, and the solvent was removed. The completion of the extraction and the purity were assured by Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) followed by column chromatography using the same solvent compositions. Among the three plants, the extract of PA had two components,, which were separated. All compounds were obtained as amorphous solids having variants of dark green color. Melting points were found to be approximately 220°C for lower component of PA and 360 oC for the upper component, 210°C for the extract of PR and 300°C for that of PZ.

2.4.2. Preparation of Nanoforms

The four components from the ethyl acetate extract were converted to nanoforms by solvothermal and sonication methods. For the solvothermal method, 0.5g of the finely powdered substance was taken in a round-bottom flask and refluxed with 20 mL of ethyl acetate with constant stirring for an hour. The solvent was removed. For the sonication method, 0.5g of the substance was taken in 5 mL ethyl acetate in a beaker and was sonicated for 30 minutes. The solvent was removed. The nanoforms were characterized by UV-Visible spectroscopy and SEM analysis. An antibacterial study of extracts and their nanoforms against E. coli bacteria was performed by the disk diffusion method. Here, disks (10 mm diameter) saturated with the sample solutions were placed over the Mueller-Hinton agar plate inoculated with the bacterial strain and incubated at room temperature for 12h. At the end of the incubation period, the inhibition zones are measured and recorded.

2.4.3. Preparation of Nanoform Impregnated Chitosan

Antibacterial study revealed that all three compounds exhibited antibacterial properties in their nanoforms. However, the extract of PZ had an appreciable high effect in its nanoforms. So the nanoform of this compound was impregnated into chitosan. To prepare this, 2.5g of chitosan was dissolved in 1% (v/v) 10 mL acetic acid, and 400, 600, and 800 μL of ~ 3% solution of both nanoforms of PZ in ethyl acetate was added to the chitosan solution by stirring. After incorporation of the nanoform, the solution was stirred for 1h at ambient temperature temperature followed by sonication for 10 min. The resulting solution was then subjected to antibacterial test against E.coli as per the aforesaid procedure.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

3.1. UV-Visible Spectroscopy

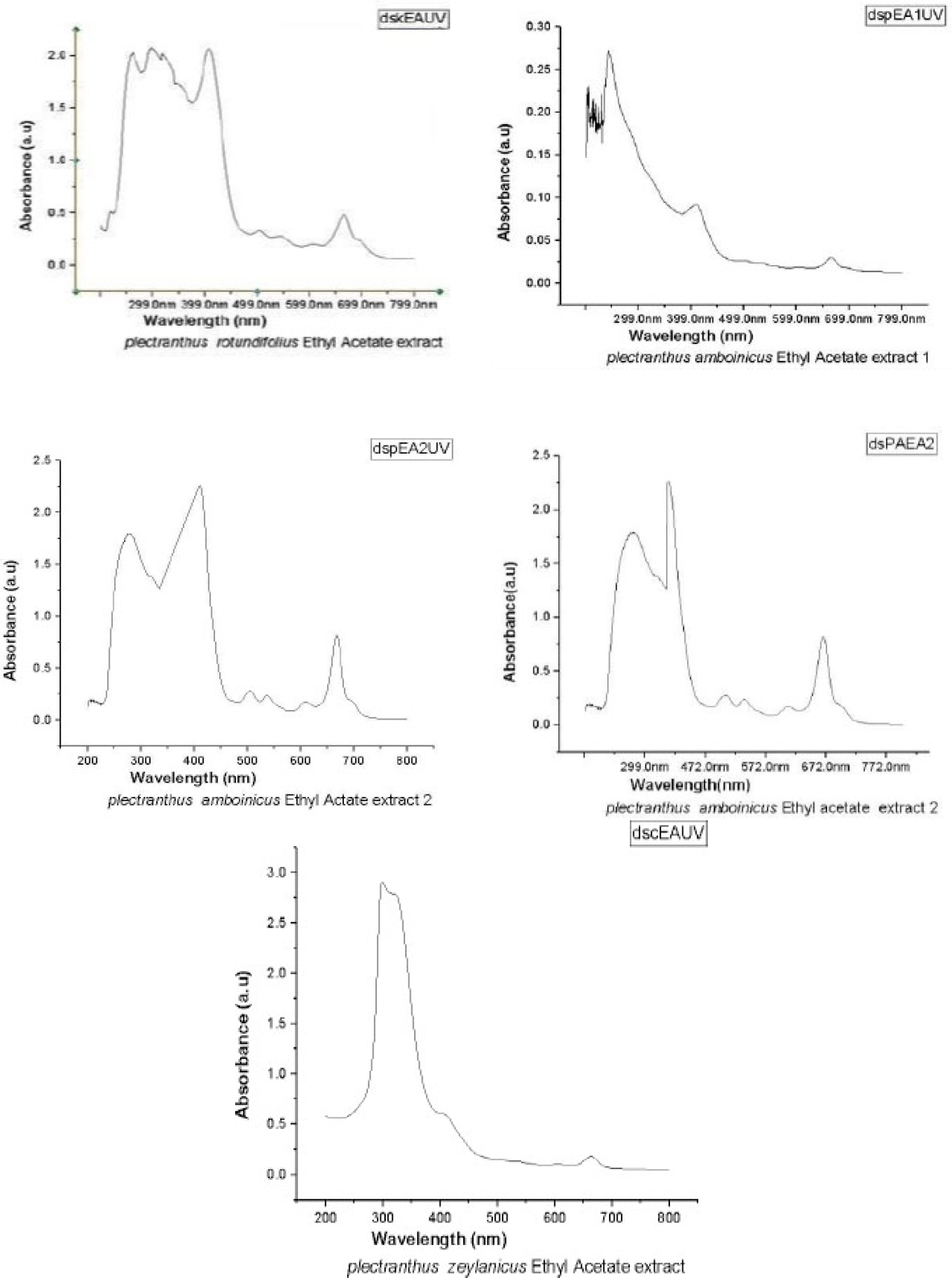

Figure 1 shows the UV spectra of ethyl acetate extractions of PA, PR, and PZ. Almost all compounds show two major peaks representing phenyl and carbonyl (approximately 300 nm for carbonyl and approximately 250 nm for phenyl groups). The second component of PA, and the component of PR has absorption in the visible range to.

UV-Visible spectra of ethyl acetate extracts 1 and 2 of PA, PR and PZ.

3.2. UV-Visible Spectrum of Nanoforms

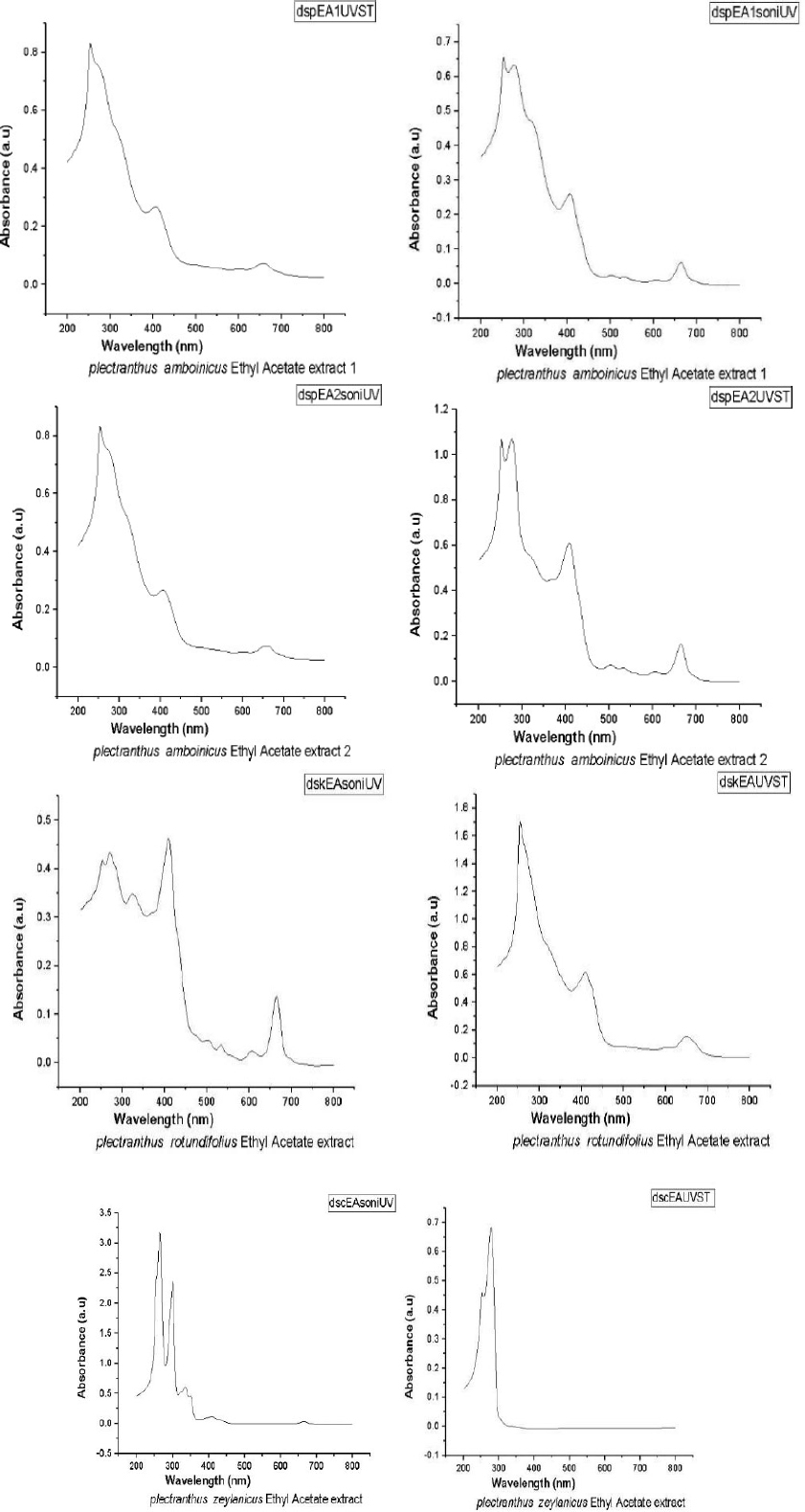

Figure 2 gives the UV-Visible spectra of the nanoforms of the ethyl acetate extracts of samples were obtained using both solvothermal (ST) and sonication (SN) methods. It is clear that both peaks are predominant, indicating the compounds do not decompose while being made into its nanoforms. There is no change in the peak values as indicated in the spectra. Hence there is no new compound has been formed.

From Table 1 it is observed that the band gap for ethyl acetate extract 1 of PA obtained by sonication and solvothermal processes are the same. This clearly indicates that in both methods, we were able to obtain nano compounds of the same dimension. In the case of second component of the extract of PA, the band gap values are found to be different. A higher value is shown by the solvothermal process, which indicates its efficiency as a better method over sonication.

For the component of the extract of PR, the band gap values are different. Solvothermal method has a higher value than the other. But for that obtained from PZ, the values are considerably different compared to the above three compounds. By the same process, better nanoparticles are obtained for the compound obtained from PZ (Figs. 3 and 4).

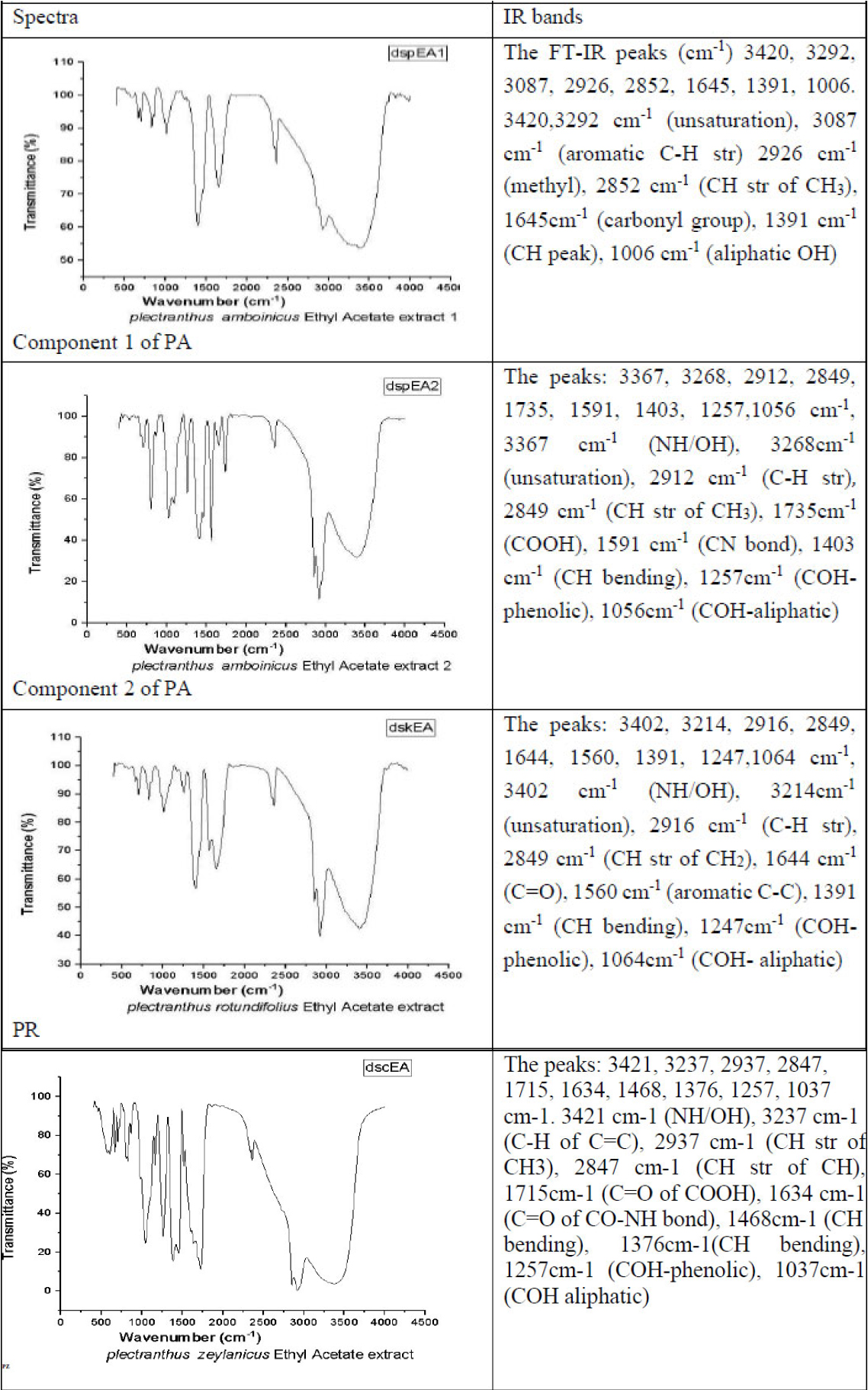

3.3. IR Spectroscopy

3.3.1. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra

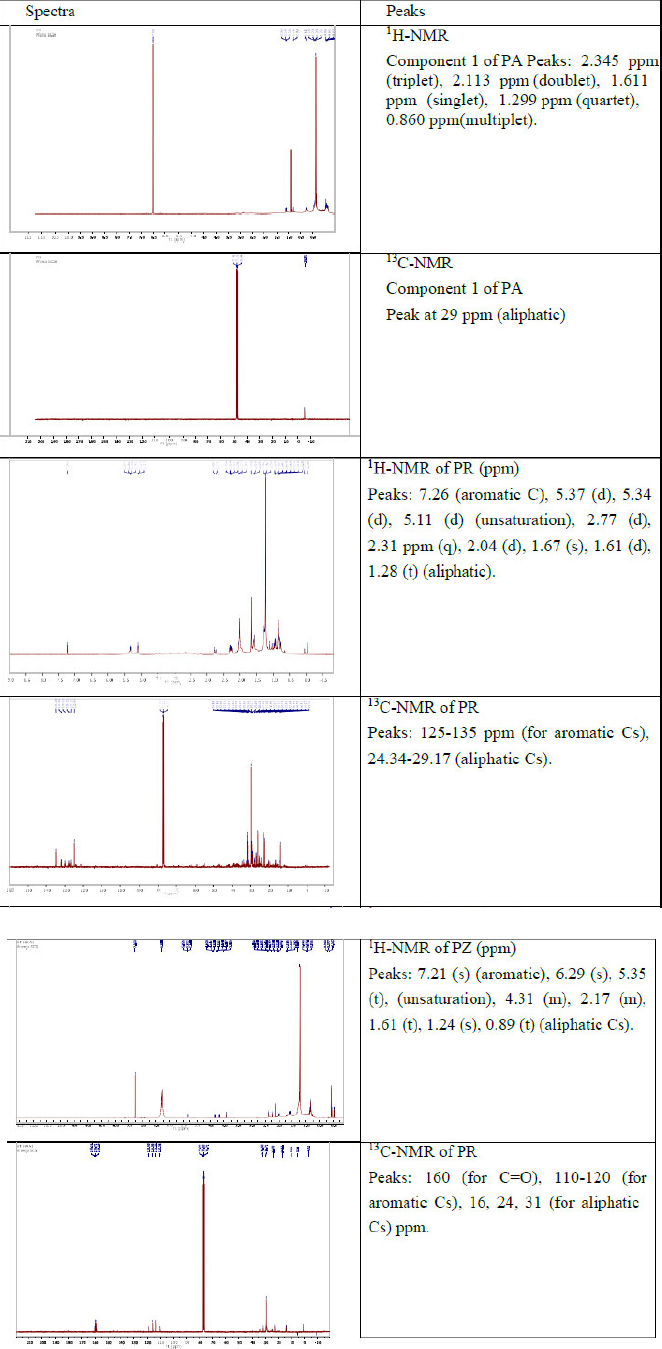

Figure 4 shows 1H and 13C NMR spectra of compounds obtained from ethyl acetate extracts of PA, PR and PZ.

UV-Visible spectra of nanoforms ethyl acetate extracts obtained by solvothermal (ST) and sonication (SN) methods of PA, PR and PZ.

| S.No. | Compound | Code | Band Gap (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | dspEA1SN | PA 1 | 2.69 |

| 2 | dspEA1ST | PA 1 | 2.69 |

| 3 | dspEA2SN | PA 2 | 2.67 |

| 4 | dspEA2ST | PA 2 | 2.72 |

| 5 | dskEASN | PR 1 | 2.66 |

| 6 | dskEAST | PR 1 | 2.71 |

| 7 | dscEASN | PZ 1 | 3.37 |

| 8 | dscEAST | PZ 1 | 4.15 |

FT-IR spectra of ethyl acetate extracts of PA, PR and PZ.

1H and 13C NMR spectra of compounds obtained from ethyl acetate extracts of PA, 219 PR and PZ.

3.3.2. Liquid Chromatography – Mass Spectra

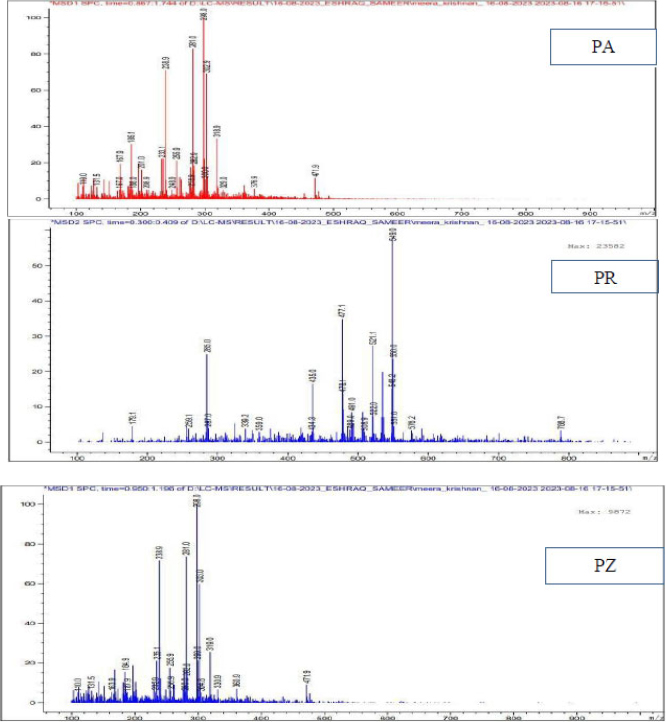

Figure 5 shows LC-MS spectra of ethyl acetate components PA (compound 2), PR and PZ.

3.3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy

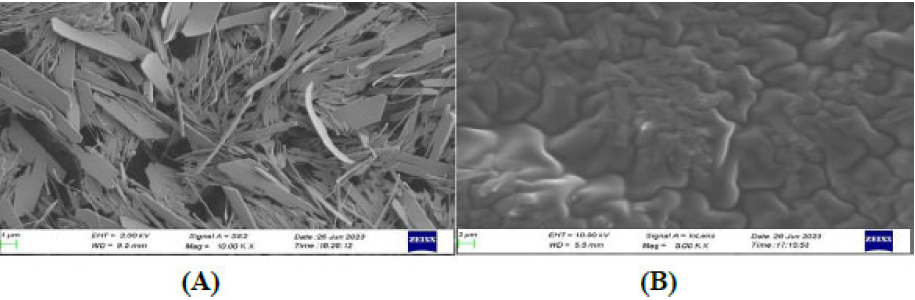

Nanoforms of the compounds obtained by the ethyl acetate extract of 1, 2, and 3 were prepared to evaluate their antibacterial activity potential. As a representative, SEM images were taken for PZ, expecting that the same size could be obtained for all three samples.

Figure 6 shows the SEM images of nanosized PZ prepared by different processes. In both cases, we could obtain the size on the nano level. The structure of the nanoparticles obtained by both processes was found to be different. By the sonication process, a flakelike structure was obtained, whereas solvothermal process gave close-packed wedge melted flakes.

LC-MS graphs of the 2nd component of the ethyl acetate extract of all the three compounds. The maximum molar weight obtained is 471, 549 and 471 for PA, PR and PZ. The most abundant peaks observed for the above are at 298, 549, and 298.

SEM images of nano PZ by (A) sonication and by (B) solvothermal process.

3.4. Antibacterial Effectiveness of Crude Extracts, its Nanoforms, and Nanoforms Impregnated Chitosan

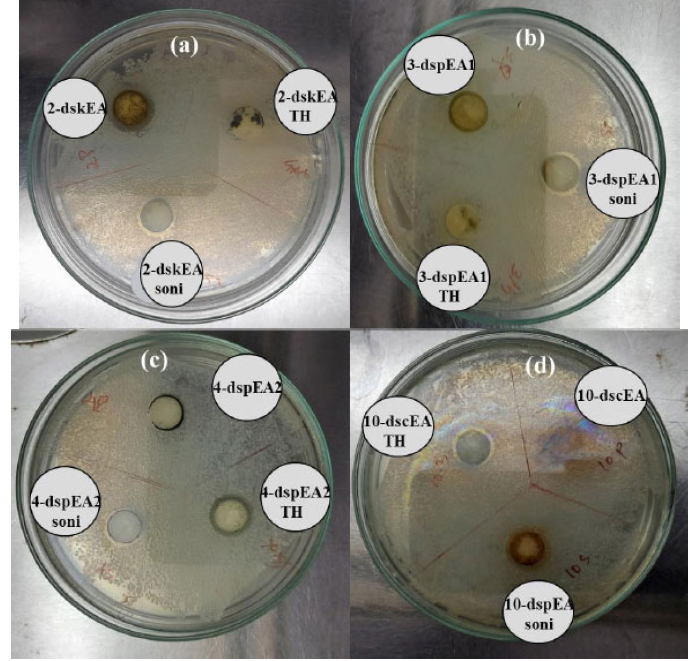

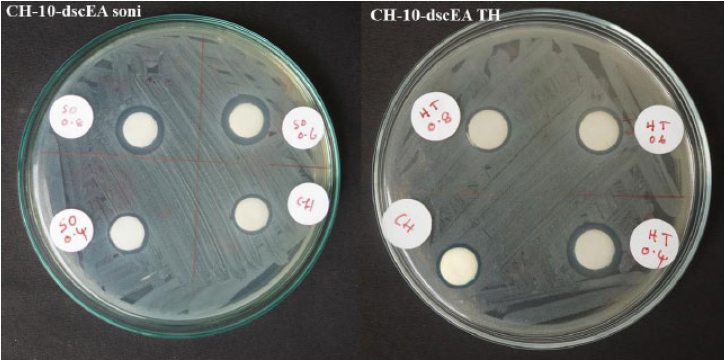

Plants in the Plectranthus family are well known for their antimicrobial actions. Keeping This in mind, the ethyl acetate extracts of PR, PA, and PZ, along with their nanoforms produced via sonication and solvothermal process were tested for their inhibition towards the E.coli growth. Generally, a gram-negative pathogenic bacterium found in contaminated food and water causes food-borne illnesses. (Fig. 7) and Table 2 revealed that the crude extract of PR (2-dskEA) and the upper component of crude extract of PA (3-dspEA1) and their nanoforms (2-dskEA soni and 3-dspEA1 soni) obtained via sonication exhibit moderate antibacterial activity, whereas the nanoform resulting from the solvothermal process exhibited negligible antibacterial effect, indicating its susceptibility to bacterial growth. Though the lower component of crude extract of PA (4-dspEA2) and the extract of PZ (10-dscEA) were not active against E.coli, their nanoforms (4-dspEA2 TH, 4-dspEA2 soni, 10-dscEA TH, and 10-dscEA soni) have significantly resisted the bacterial growth [29]. Among the samples, 10-dscEA TH and 10-dscEA soni with inhibition zone diameter 13 mm were incorporated with chitosan to prepare CH-10-dscEA TH and CH-10-dscEA soni. The antibacterial effect of these solutions are studied and the results are shown in Fig. (8) with corresponding inhibition zone diameter in Table 3. Chitosan, a deacetylated derivative of chitin, is a cationic linear polysaccharide consisting of D-glucosamine and N-Acetyl-D-glucosamine units. Researchers have immense interest in these materials impregnated on chitosan due to its biodegradability, biocompatibility and eco-friendliness with non-toxicity and antibacterial efficiency [30]. Bare chitosan shows an inhibition zone of 12 mm diameter against E.coli as a result of its easy entry into the microbial cell, followed by the destruction of the metabolic activity. Well defined clear inhibition circle compared to that of CH only (control) depicts its improved potential for antibacterial activity after the impregnation of 10-dscEA TH and 10-dscEA soni. This is the result of the synergetic effect of CH and the nanoforms due to the electrostatic interaction between the negatively charged bacterial membrane and the positively charged entities in the sample solution, which in turn disturbs the bacterial action and hence significantly reduces its growth.

Antibacterial activity of (a) crude extract and its nanoform of PR (b) component 1 and nanoforms (c) component 2 and nanoform of extract of PA and (d) crude extract and its nanoform of PZ against E. coli..

Antibacterial effect of Chitosan and nanoforms of PZ incorporated chitosan against E. coli..

| Samples | Inhibition Zone (mm) |

|---|---|

| 2-dskEA | 15 |

| 2-dskEA TH | Nil |

| 2-dskEA soni | 12 |

| 3-dspEA1 | 12 |

| 3-dspEA1 TH | Nil |

| 3-dspEA1 soni | 13 |

| 4-dspEA2 | Nil |

| 4-dspEA2 TH | 14 |

| 4-dspEA2 soni | 11 |

| 10-dscEA | Nil |

| 10-dscEA TH | 13 |

| 10-dscEA soni | 13 |

| Samples | Inhibition Zone (mm) |

|---|---|

| CH CH-10-dscEA TH |

12 |

| 400 μL | 15 |

| 600 μL | 13 |

| 800 μL | 12 |

| CH-10-dscEA soni | |

| 400 μL | 12 |

| 600 μL | 15 |

| 800 μL | 16 |

Enhanced antibacterial activity points out its practical application as bioactive coatings for the preservation of fruits and vegetables [31, 32].

Samples of 400, 600, and 800 μL nanoforms of PZ incorporated chitosan were also were prepared, and their antibacterial activity was determined. Table 3 describes the inhibition zone of bare chitosan and two types of nanoforms of PZ incorporated into chitosan. In the case of nano PZ obtained by the solvothermal process, the antibacterial activity was found to decrease when, the concentration increased. At an 800 μL concentration, the value was the same as the bare chitosan. In the case of nanoparticles obtained by sonication, a reversal order was observed.

As the contraction of nano PZ increased, there was an increase in inhibition from 400 to 600 μL.

CONCLUSION

Plectranthus species have anti-inflammatory and analgesic potential. In summary, the single compounds obtained by the ethyl acetate extracts of the three plants (PA, PR, and PZ) belonging to the Lamiaceae family was subjected to an antibacterial study. Since the performance was not so predominant; nanoforms of the same were prepared by both sonication and solvothermal methods. Among the tested nanoforms, the antibacterial potency of the nanoform of PZ was found to be better. Hence, it was impregnated at various concentrations in chitosan to enhance their antibacterial activity.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: M.K., M.T.R.: Methodology; G.V.Z.: Data curation; M.N.J.: Validation; D.S., K.R.H.: Draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| UV | = Ultra violet |

| FT-IR | = Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy |

| NMR | = Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| LC-MS | = Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this research are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Grigory V. Zyryanov is thankful to the Russian Science foundation (Grant # 25-73-30016) for the financial support.